Decamped

I'm never sure how to answer the simple, making-polite-conversation question "Where are you from?", much to the interlocuter's dismay.

It's a long answer that's a short story, and as I try to spare my listener that still unedited version, I fumble on finding the highlights. Birthplace, identity, kindergarden class, nationality? What do these question-askers want to know? More to the point, what do I want to say?

It's a decamping and rerooting story that starts in Beirut and an apartment across from Palestinian camps, to New York,

and current campings-out in the apartments of patient friends who like dogs.

and current campings-out in the apartments of patient friends who like dogs.Summing myself up is no easy task, only because there's so much unknown and no defined boundaries. I'm still walking the path of self-discovery, and claim all the stops along the way, however random. Not just one fits, and they all stick in some way. It makes for some uncomfortably-existential small talk.

More on the messy ponderings later.

An even more common question is "Where do you live?" Though still rooted to New York City by an address and its correspondingly tall, thin, aluminum mailbox with an ill-fitting key, a subletted studio apartment whose awkward confines I've fled, and weekly returns down the autumnal Taconic Parkway for work, the answer is: Upstate. In an old salt-box house with a frog-hosting pond in the back.

More on that new, temporary home later.

I'm not the only one who's decamped recently. Chantal, my sister, has left Bloomington and her teaching duties at the University of Indiana, for Paris, and other, newer teaching duties at La Sorbonne.

Having crossed the larger pond, Chantal is more than yet another American in Paris. First, she's also French. Her journey is defined not only by exile, but also by return to an identity, a French self, perhaps best known until now through its strongly lived reflection in our mother, herself a cosmopolitan and traveler, whose French identity is more strongly lived every year, and whose French accent is more strongly defined, sharp and rolling, like a good vintage, every year, favorites you can't really chose among.

Chantal's a teacher, and a student, writing about exile while being, in part, in exile herself, and teaching a group of French graduate students about exilic literature.

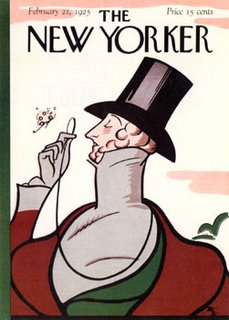

But maybe I'm giving too much away. An introduction should tantalize yet not satiate. In preparation, I've been reading other dispatches, among them Janet Flanner's "Letters from Paris" written for the New Yorker magazine, starting when it was brand new.

Because I always love a backstory, and because I'm always imminently curious about how writers' writing find a home and a platform, (and from there shine a light on my search) I'll include the path for Janet Flanner's "Letters" into the New Yorker.

As readers, we can thank the wife of the New Yorker's editor, and a now obscure, yet not defunct organization that fought for women to preserve their maiden names after marriage. Jane Grant, Harold Ross' (editor of the New Yorker) wife, was friends with Flanner through the Lucy Stone League, of which they were both members.

I bring up Flanner because she is a predecessor, but not a parallel. Not sure whether Chantal's dispatches will be more personal journalism or literary blog, public pronouncement or intimate letter, or a little bit of all, or none of these and something entirely different, I'm eagerly awaiting her dispatches from Paris, of which I've gotten snippets through strangely bad phone connections. She's found a new home in an old arrondissement. Perhaps all you need to know is that her apartment is in an old building, rue Geoffroy St. Hilaire, has a concierge. I know there's a story there, for starters.

Welcome to Paris, Chantal.